What is the EJ4Climate Grant Program?

The CEC established this grant program in 2021 to fund projects that target underserved and vulnerable communities, and Indigenous communities, in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, to prepare them for climate-related impacts.

The EJ4Climate Grant Program provides funding directly to community-based organizations and seeks to support environmental justice by facilitating the involvement and empowerment of communities searching for solutions and the development of partnerships to address their environmental and human health vulnerabilities, including those due to climate change impacts.

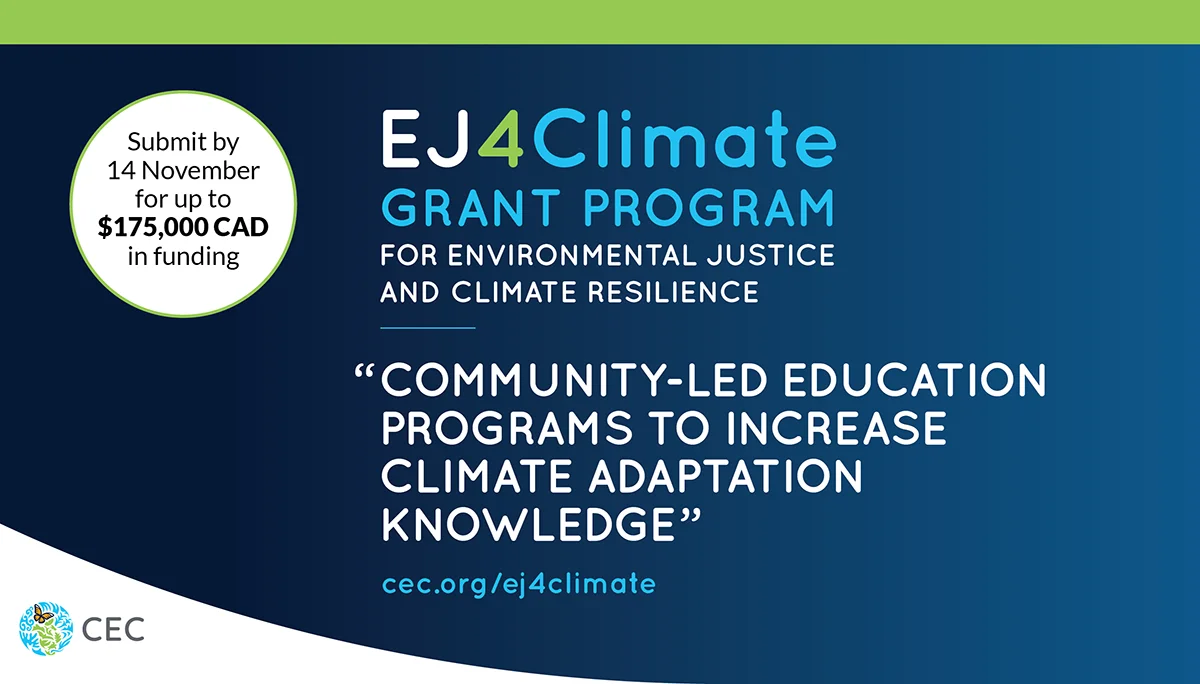

Community-led education programs to increase environmental justice and climate adaptation knowledge

For the fourth grant cycle of EJ4Climate, the CEC is calling for project proposals that will integrate community-led education programs in support of environmental justice and climate adaptation.

Education, whether formal or informal, is crucial to advance environmental justice. It is also recognized as essential in addressing the issue of climate change and a key element of climate adaptation as it enhances the adaptive capacity and empowers people with the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes necessary to take action against climate change.

Community-led education programs can enable individuals to understand and analyze their problems and include a variety of perspectives in a learning-by-sharing approach that transforms the local knowledge into innovative actions or solutions.

Community Response to the EJ4Climate Grant Program

The fourth cycle of the EJ4Climate Grant Program concluded with the selection of 12 grant recipients representing a range of communities in Canada, Mexico and the United States.

Learn more about current and previous grant recipients and their projects.

General concepts

Origins and evolution of the EJ movement

Although the precise origins of environmental justice as a concept and as a movement are widely disputed, there is broad agreement that the self-labeled “EJ” movement initiated in the United States, emerging from the Civil Rights Movement and the fight against racial segregation that began in the 1950s. The EJ movement focused on the impacts of pollution on already disadvantaged and marginalized people, setting itself apart from the more traditional environmental movement focused on the conservation of natural resources.

Specific historical events have marked key moments of the EJ movement, such as the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike, which took place in Memphis, Tennessee after two African American sanitation workers were crushed to death while performing their duties. Subsequent EJ milestones, such as the 1982 sit-in protesting the Warren County PCB Landfill, began to consolidate the identity, narrative and terminology of the environmental justice movement, responding to evidence that demonstrated disproportionate rates of pollution with neighborhoods where African Americans and other people of color were predominantly living.

One key meeting, that catapulted the EJ movement onto the national stage in the United States, as well as drawing attention regionally and globally, was the 1991 First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. Hundreds of activists from across the United States, Canada, Mexico, Central America and beyond gathered in Washington, D.C. for four days, ultimately issuing the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice, which are still considered pillars of the EJ movement today.

At its core, and since its origins, environmental justice is about protecting people from pollution and harm. It’s about racism, discrimination and human rights violations due to inequitable impacts of environmental degradation and pollution. The broader, global environmental justice movement has evolved in unison with a parallel international environmental movement more broadly associated to human rights and environment-based advocacy that emerged in the late twentieth century, which resonated with the EJ movement and embraced EJ-compatible narratives.

Definitions of EJ in Canada

Several official Canadian definitions of environmental justice have recently appeared. Environment and Climate Change Canada’s (ECCC) Glossary on Climate Change and Public Health, defines EJ in the following manner:

“The principle under which every person, regardless of their race, ethnic origin, religion, sex or gender, age, social class or socioeconomic status, is entitled to equitable protection under environmental laws and can participate in environmental decision-making processes in their community.”

ECCC also offers a definition of environmental “injustice” which serves to contextualize the understanding of environmental justice in the Canadian context (highlighting equity of risk, human health and climate vulnerability):

“Environmental injustice refers to inequitable exposure to environmental risks, including to health risks, making some populations more vulnerable to climate change.”

A more recent definition of environmental justice (also defined relative to environmental “injustice”) can be found in Canada’s 2023 National Adaptation Strategy as follows:

“Environmental Justice: Environmental injustice reflects the procedural and geographic discrimination of Indigenous, Black, Racialized, religious, low-income, 2SLGBTQI+, women, and other marginalized communities such as the very young, older adults, or people who experience structural inequity, poverty, or isolation, placing said communities in close proximity to environmental hazards, often resulting in direct health impacts. These same communities are also under-represented in environmental decision-making spaces.”

The guiding principles of the National Adaptation Strategy also reference environmental justice (in a climate context) by saying:

“Adaptation efforts must act to advance climate justice and more broadly environmental justice. This includes addressing and minimizing social, gender, racial, and intergenerational inequities which requires diverse perspectives at the table—including youth and persons with disabilities. It also includes prioritizing populations and communities at greater risk of climate change impacts—e.g., due to historical and ongoing practices and policies that shape lived experiences, capacity and access to resources. As we build systems and solutions that are more climate resilience, we have the opportunity to address systemic inequities that make people more vulnerable.”

Definitions of EJ in Mexico

The term environmental justice appeared in Mexico in the 1990s and has generally been utilized in relation to issues of procedural justice. Currently, two government programs in Mexico in the environmental sector offer a definition of EJ.

The 2020–2024 Environment and Natural Resources Sectoral Program (Promarnat) 2020-2024 defines EJ narrowly, linked to judicial and procedural elements, as:

“The obtention of an opportune judicial solution to a specific environmental conflict, taking into account that all persons must begin with the same conditions to access environmental justice”.

PROFEPA’s 2021–2024 Procurement of Environmental Justice Program proposes a definition of EJ that includes additional and broader aspects related to EJ, defining EJ as:

“The rights of nature for all; individuals, families, communities, companies and other human groups in relation to the environment, considered as a common good, but in exchange of responsibilities and legal obligations these responsibilities and obligations oftentimes are grouped under the notion of “social and environmental responsibility”, the liberty to exploit the environment ends where it threatens others (and so it is an obligation not to over-exploit a resource), and where the environment (biodiversity, natural habitats, and genetic diversity) would be themselves threatened by human activities.”

Definitions of EJ in the United States

The term environmental justice did not appear in regular use in the United States until the mid-1990s. Prior to this, the issue of EJ was referred to either as “environmental equity” or as “environmental racism.”

One of the most recent US government definitions of EJ is in Executive Order 14096, titled Revitalizing our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All. In this April 2023 order, environmental justice is defined as follows:

“Environmental justice” means the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability, in agency decision-making and other Federal activities that affect human health and the environment so that people: (i) are fully protected from disproportionate and adverse human health and environmental effects (including risks) and hazards, including those related to climate change, the cumulative impacts of environmental and other burdens, and the legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers; and (ii) have equitable access to a healthy, sustainable, and resilient environment in which to live, play, work, learn, grow, worship, and engage in cultural and subsistence practices.”

Indigenous environmental justice

Is there a specific framework or lens to look at environmental justice from an Indigenous perspective? Are Indigenous rights issues also EJ issues? Is one the subset of the other, or are they interrelated? There is a growing body of literature and discussion on Indigenous Environmental Justice (IEJ). Indigenous analysis on the current shortcomings and deficiencies of Western-influenced development models in the past and present is strongly anchored in colonial history and persistent colonial and settler governance systems, which most Indigenous communities argue must be deconstructed, or decolonized, in order to re-establish a sustainable balance in the natural, spiritual and human worlds. This de-constructionist view of the present state of affairs guides a majority of advocacy about Indigenous rights and subsequently influences IEJ approaches.

We can identify several EJ-relevant aspirational goals in Indigenous rights advocacy, for example in the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), such as the rights and pursuits for diversity, justice and access to justice, non-discrimination, equity, participation in decision-making, access to information, physical and mental health, redress, reparations and compensation, as well as intersectional considerations for vulnerable groups (including youth, elders, women and people with disabilities), non-discriminatory conservation of the environment and the proper management of toxic waste.

One gray area from an EJ framework analysis for specific IEJ issues concerns Indigenous Peoples’ calls for autonomy, sovereignty, self-determination, self-governance and the prioritization of the deconstruction of colonial legacies. In contrast to these aims of many Indigenous Peoples, many EJ leaders, although similarly critical of the legacies and continuing inequities of governance systems, are instead seeking inclusion and participation in existing governance systems, rather than autonomy or self-governance.

Climate change adaptation (or climate adaptation) refers to actions that help reduce vulnerability to the current or expected impacts of climate change like weather extremes and hazards, sea-level rise, biodiversity loss, or food and water insecurity.

Many adaptation measures need to happen at the local level, so rural communities and cities have a big role to play. Such measures include planting crop varieties that are more resistant to drought and practicing regenerative agriculture, improving water storage and use, managing land to reduce wildfire risks, and building stronger defences against extreme weather like floods and heat waves.1

We understand “underserved communities” as “populations sharing a particular characteristic, as well as geographic communities, that have been systematically denied a full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic, social, and civic life…”and includes individuals “such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality.”1

See also California’s definition of “climate vulnerability” developed for its Integrated Climate Adaptation and Resiliency Program.2