During the 2019-2020 season, the monarch butterfly population occupied 2.83 hectares of forest

This press release was originally issued by Mexico’s Natural Protected Areas Commission

- A total of 11 monarch butterfly colonies (3 in Michoacán and 8 in Mexico State) were recorded, including a new colony in the El Potrero ejido, Municipality of Amanalco de Becerra, Mexico State.

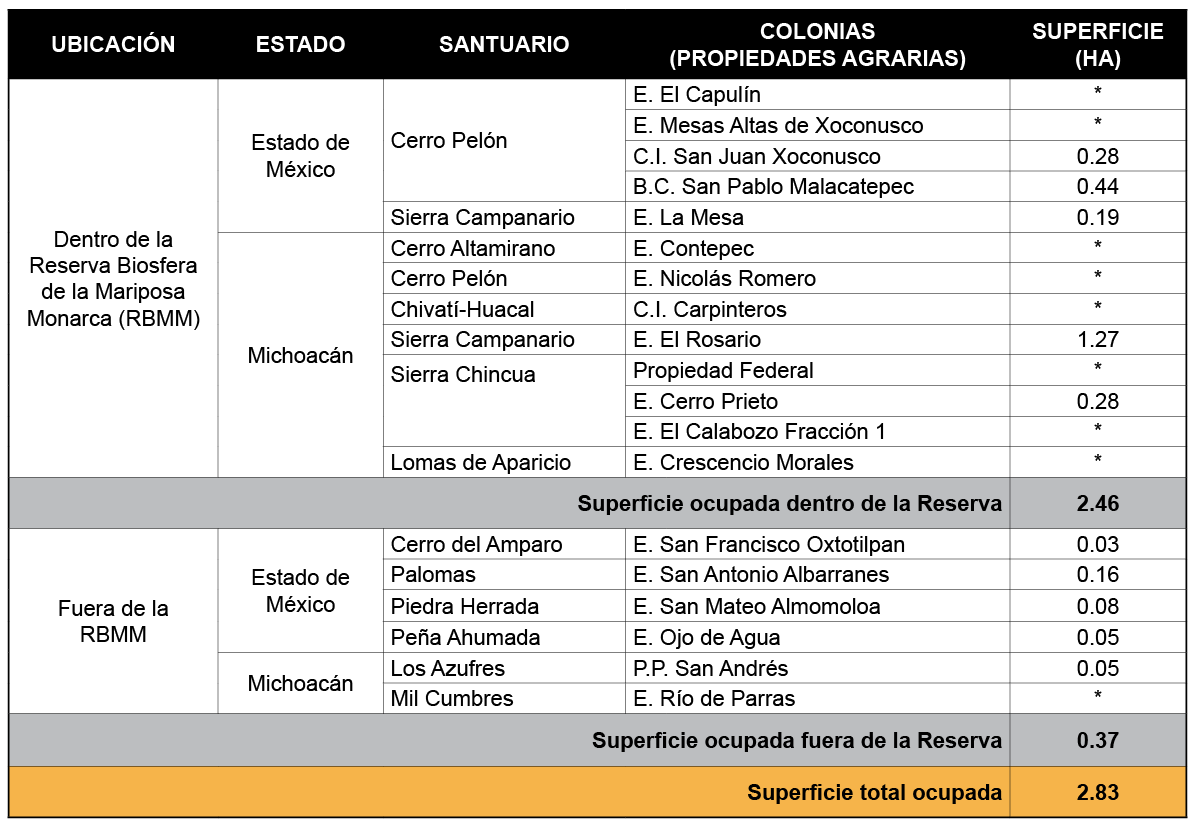

- The colonies occupied a total of 2.83 hectares (ha) of forest, with 5 colonies (2.46 ha) inside the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR) and 6 colonies (0.37 ha) outside it.

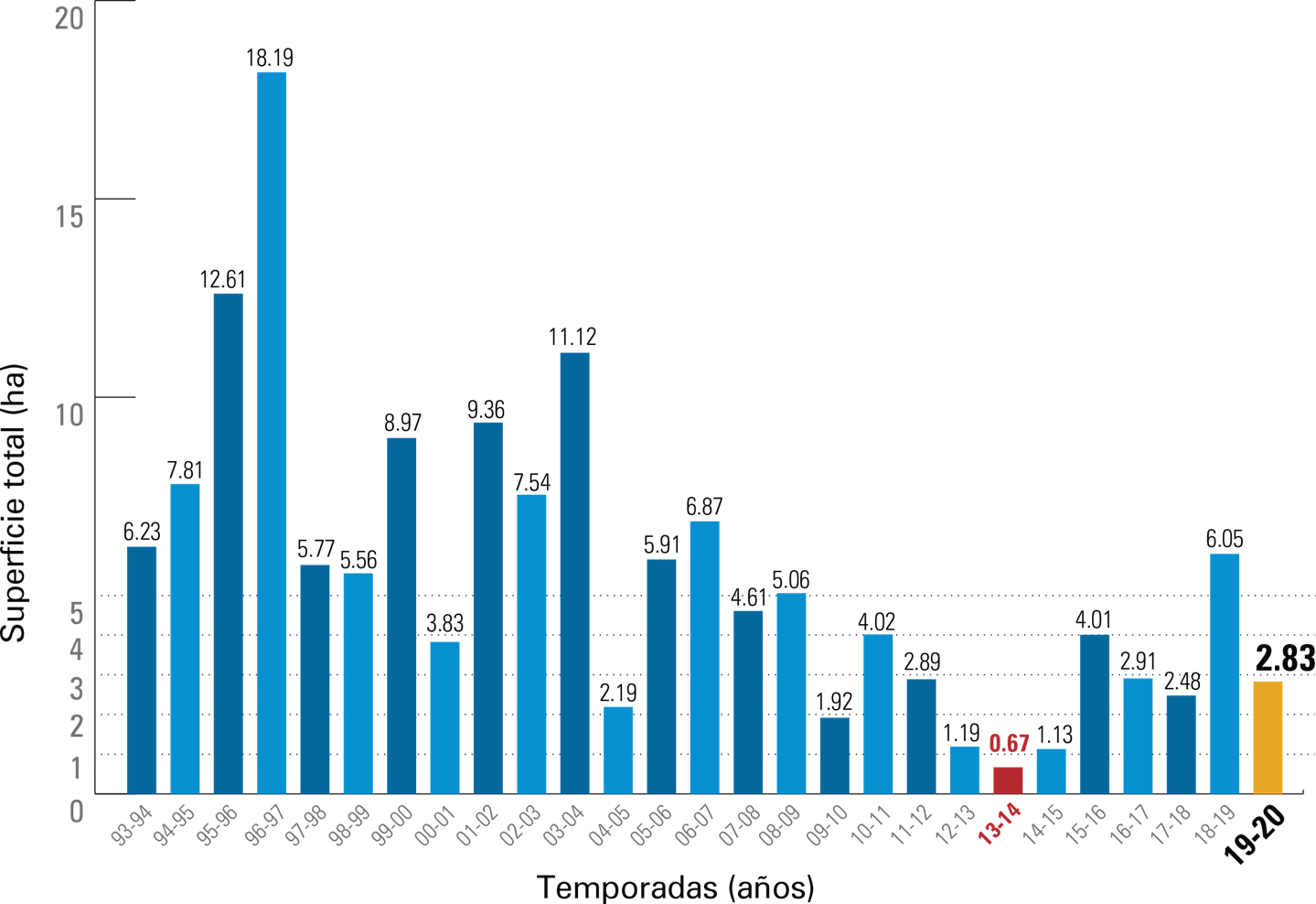

- The population is stable and the clusters that formed were larger than in previous years. This area represents a shrinkage of 53.22% from the area occupied in December 2018 (6.05 ha).

During the 2019–2020 season, eleven monarch butterfly colonies (3 in Michoacán and 8 in Mexico State) were recorded, occupying 2.83 ha, of which 5 colonies (2.458 ha) were within the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve and 6 colonies (0.36 ha) outside it. This represents a 53.22% shrinkage with respect to the area occupied in December 2018 (6.05 ha), according to the Mexican Protected Natural Areas Commission (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas—CONANP) and the Alianza WWF-Fundación Telmex Telcel.

The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve continues to be a critical site for wintering monarchs, harboring 87% of the total monarch population during this season. The El Rosario ejido (Sierra Campanario sanctuary) colony recorded the largest area, with 1.27 ha, while the El Potrero ejido (Cerro de la Antena sanctuary) had the smallest (0.001 ha). This latter colony is a new record within the Valle de Bravo, Malacatepec, Tiloxtoc, and Temascaltepec Natural Resources Protection Area. For the second time, we recorded a colony in the Ojo de Agua ejido, with 0.049 ha (Table 1). The Atlautla colony (0.01 ha) was recorded within the area of influence of Iztaccihuatl-Popocatepetl National Park.

Roberto Aviña Carlín, Director of Conanp, stated that the effort to conserve this spectacular migratory phenomenon has been the result of coordination between Mexico and the governments, academic sectors, and civil societies of Canada and the United States since February 2014. It was then, at the North American Leaders’ Summit held in Toluca, Mexico State, that a trilateral working group was formed to counteract the population decline recorded during the 2013–2014 season, amounting to a 0.67-ha decrease in the total forested area occupied by the monarch butterfly in its wintering sanctuaries.

“In recent winters, the butterflies have occupied an average of about 3 hectares of forest. The winter of 2018–2019 was very good, with 6.05 hectares occupied. It was, however, atypical in that the first generation of spring 2018 butterflies in Texas encountered favorable weather conditions and was able to repopulate all the North American breeding sites,” said Jorge Rickards, Executive Director of WWF México.

“The recent reduction in the monarch population is not alarming, but we have to make sure that it does not become a trend in future years. Conservation is long-term work. The Alianza WWF-Fundación Telmex Telcel has been measuring the woodland area occupied in winter by the butterflies for over 16 years, and monitoring the status of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve for 20 years. The latter continues to offer good wintering habitat, with very low levels of illegal logging, amounting to 0.43 ha in 2018‒2019. We are committed to continuing our work alongside everyone involved in the conservation of this species, its habitat, and the human communities that depend on it,” concluded Mr. Rickards.

Monarch butterflies migrate over 4000 km from Canada and the United States to winter in the forests of Mexico from November to March. The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve is also home to 132 species of birds, 56 species of mammals, 432 species of vascular plants, and 211 species of fungi. These forests also act as a water reserve for more than 4.1 million people in Mexico City and its metropolitan area.

The main threats to the monarch in North America are breeding habitat loss in the United States due to declining milkweed populations, caused by indiscriminate herbicide use and land use changes; forest degradation on the wintering grounds in Mexico due to historical clandestine logging and weather-related tree fall; and extreme climatic conditions in Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

The first Mexican monarch butterfly sighting for the 2019‒2020 season was recorded on October 7 at Acuña, Coahuila, and they arrived punctually at their wintering sanctuaries at the end of October.

There was no extreme weather this winter that could have jeopardized the butterfly population. The only phenomenon of note was the cold front (number 32) on 19‒21 January 2020, associated with a mass of cold air, a sharp drop in temperature, rainfall, and strong gusts of wind. There were even ice pellets in some parts of the region, but without significant consequences for the colonies.

The first indications of butterfly breeding were recorded during the last week of January 2020 and as of the second week of February. Volunteer monitors organized by the Guanajuato state government observed the first monarchs migrating towards northern Mexico and the southern United States in search of feeding and egg-laying habitat. Groups of monarchs are currently being seen along the highways, so it is requested that anyone who sees them reduce their speed to 40 miles per hour.

The Correo Real program and the National Monarch Butterfly Monitoring Network have monarch records starting in late February on their spring migration through the states of Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, Querétaro, Hidalgo, and Coahuila.

May 2019 saw the publication of the Monarch Butterfly Conservation Action Plan for Mexico. This, the country’s the master plan, lays out 147 priority measures to be taken, which are divided into six strategic headings, defined in a participatory manner, for conservation of the butterflies along the migratory route and on the Mexican wintering grounds. These headings are: 1) economics of conservation; 2) restoration and conservation; 3) research and monitoring; 4) inspection and enforcement; 5) civic participation, communication, and culture for conservation, and 6) coordination and funding.

There are still some clusters and individual butterflies to be seen amid the pines and sacred firs at some sites open to tourism in the states of Mexico and Michoacán. Conanp invites members of the public to continue enjoying this exceptional natural phenomenon, always following the recommendations of local guides to ensure that the tourist’s stay and experience is a pleasant one. The monarch butterfly tourist season closes 31 March 2020.

The National Commission for Protected Natural Areas invites you to participate in the #ProtejamosAlasMonarca campaign. The monarch butterfly is currently passing through your city, so keep your eyes open: scan the skies, your school garden, and your local parks, and you may see them. Record your observations on the National Monarch Butterfly Monitoring Platform, downloadable at the following addresses:

iOS: https://apps.apple.com/cl/app/redmonarca/id1435524759

Android: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.RedMonarca.www&hl=es_MX

With this app, you can help map the monarch’s migratory route through Mexico and conserve this spectacular natural phenomenon. You can also do this through the “Naturalista/Monarca” platform, or send your records to “Correo Real” at correo.monarca@gmail.com. In this way, you will be making a contribution to knowledge about the presence of monarch butterflies in our country.

To learn more about this species, we invite you to visit SoyMonarca.mx, a site containing a wealth of information about the biology, breeding, habitat, and migration of this species, including scientific papers and conservation initiatives.

In view of its “exceptional universal value,” the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.

Wintering colonies and forested area occupied by monarch butterflies

Forest occupation on wintering grounds, 2019–2020

[Figure 1 legend]

[Figure 2 legend]

Total area (ha)

Season (years)

About the CEC

The Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) was established in 1994 by the governments of Canada, Mexico and the United States through the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation, a parallel environmental agreement to NAFTA. As of 2020, the CEC is recognized and maintained by the Environmental Cooperation Agreement, in parallel with the new Free Trade Agreement of North America. The CEC brings together a wide range of stakeholders, including the general public, Indigenous people, youth, nongovernmental organizations, academia, and the business sector, to seek solutions to protect North America’s shared environment while supporting sustainable development for the benefit of present and future generations

The CEC is governed and funded equally by the Government of Canada through Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Government of the United States of Mexico through the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, and the Government of the United States of America through the Environmental Protection Agency.