2 Feature Analysis: Off-site Transfers to Disposal in North America, 2014–2018

2.4 Analysis of Off-site Transfers to Disposal, 2014–2018

2.4.7 Tracking transfers to disposal, from source to recipient

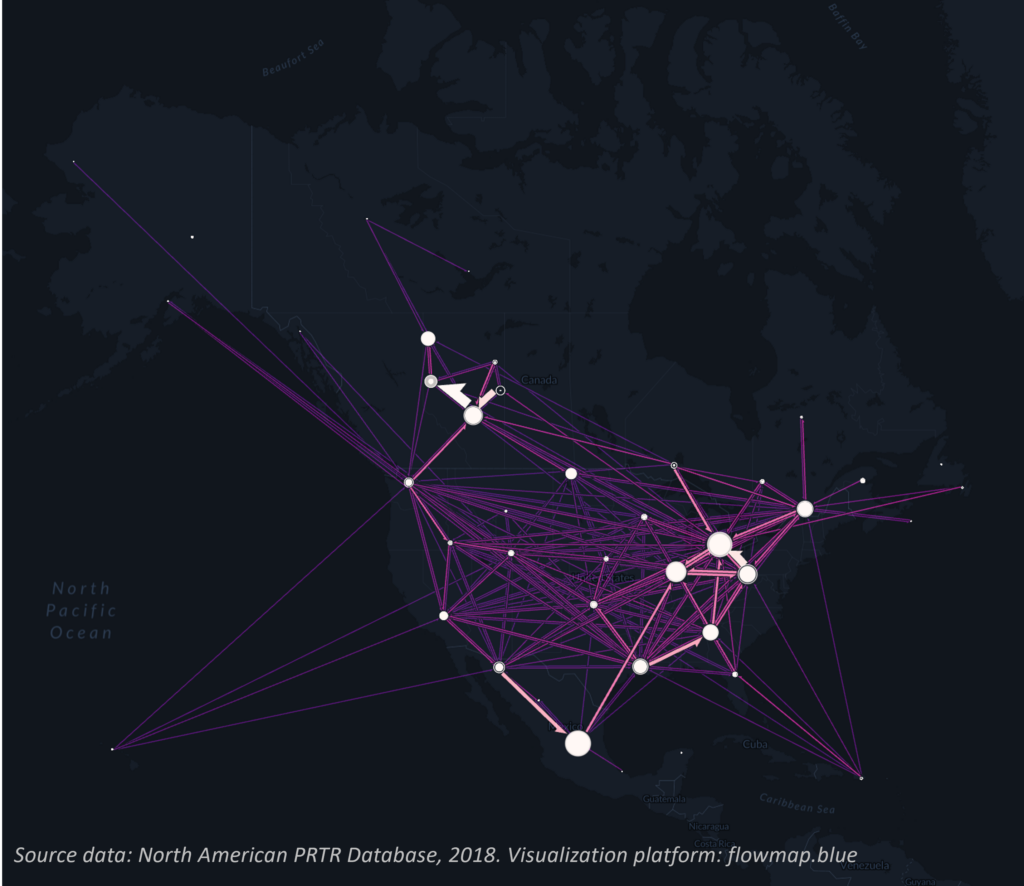

This feature chapter on transfers to disposal has focused on the amounts reported and thus, on the source (or sending) facilities. However, as discussed above, it is equally important to have accurate information about the final destinations (or recipients) of these wastes transfers. For the first time, the CEC has compiled trinational PRTR data for all source and recipient facilities involved in transfers to disposal, both within and across borders. The map in Figure 23 illustrates the flows of these transfers within North America in 2018.[73]

Figure 23. Flows of Transfers to Disposal within North America, 2018

An initial exploration of these data provides interesting information about both the sources and recipients of transfers to disposal. For example, in many cases source facilities indicate inaccurate, or no, locational information (e.g., city, province/state/territory) for the recipient; or they provide generic recipient facility descriptions in lieu of an official name (e.g., “landfill,” “agricultural land,” “injection well No. 2,” “transfer station,” “garbage”).

Among the clearly identified recipients of transfers to disposal are waste management facilities, cement plants, smelters, landfills, underground injection wells, wastewater treatment plants, chemical manufacturers, farms and agricultural land, and transfer stations. However, website information for some of these recipients raises questions about their suitability relative to the wastes transferred to them. For example, certain landfills specify that they are not designed to receive hazardous waste, yet the data show that they receive pollutants—often in large quantities—that can potentially pose risks to humans or the environment, depending on whether they are in a form rendering them suitable for disposal in areas not designed for hazardous waste (e.g., stabilized, or inert).

Prioritizing pollutants of common concern

The analyses of data for transfers to disposal have revealed similarities among the three countries in the sectors and pollutants reflected in these transfers, as well as important gaps in data across the region. While there are certainly differences in their scope and size, most of the top reporting sectors (e.g., iron and steel mills/ferroalloy manufacturing, oil and gas extraction, waste management, electric utilities) operate in all three countries. Therefore, one can conclude that the gaps in data across the region for these sectors are in large part due to differences among Canadian, Mexican and US PRTR reporting requirements.

Much of the emphasis in these analyses is on the substances reported in largest proportions—for example, metallic compounds such as zinc and manganese, along with hydrogen sulfide, nitric acid/nitrate compounds, and total phosphorus. However, as mentioned earlier, while industrial facilities transferred more than 400 pollutants to disposal between 2014 and 2018, there are wide disparities in the number of substances subject to reporting in each country and therefore, in the data available for analysis.

Of equal or greater importance than the volume of pollutants transferred to disposal is their potential for negatively affecting human health or the environment. As mentioned earlier, a pollutant’s inherent toxicity, its potential to persist in the environment or alter it in some way, the route of exposure, and other factors must be considered when trying to assess risk. Among the pollutants transferred to disposal by North American facilities between 2014 and 2018, 210 are known for their potential to cause harm to human health or the environment—that is, they can affect human development or reproduction, are known or suspected carcinogens, or have the potential to persist in the environment and biomagnify within the food chain.

Varying PRTR reporting requirements for these substances hinder our ability to fully understand the risks related to their disposal. A related issue is the fact that, depending on the country, certain pollutants are reported as groups; for example, the chromium compounds group includes hexavalent chromium compounds, which are extremely toxic, along with other, less toxic chromium compounds (only under NPRI are hexavalent chromium compounds reported separately). This adds to the difficulty of understanding potential contamination issues that may arise from the disposal of very toxic substances (not to mention the risks posed by their accumulation over time).

PRTRs offer the possibility of tracking pollutant releases and transfers, as well as contributing to raising awareness about known or emerging issues associated with them. For example, information has come to light about the environmental and human health impacts of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a group of synthetic chemicals manufactured and used in food packaging, firefighting foams, heat-, water- and stain-repellent products, and other industrial processes worldwide for more than 50 years. Certain PFAS, which are also known as “forever chemicals” because they can accumulate and remain in the human body for long periods of time, have been associated with adverse human health outcomes such as cancer, thyroid and liver problems, and birth defects.[74] Recently, high levels of PFAS have been found in the sewage sludge-based biosolids applied to farmland in the United States and elsewhere (OECD 2013).[75]

During the 2021 meeting of the UNECE’s International PRTR Coordinating Group, which helps coordinate the efforts of international organizations, governments, and other interested parties relative to the development of PRTR systems, it was recommended that certain PFAS be included in PRTR pollutant lists. In recognition of this emerging issue, the United States added 172 PFAS to the TRI for the 2020 reporting year.

The ability to access accurate and complete data relative to the management of pollutants of common concern by North American industrial sectors can support policies and actions to prevent not only their inadvertent release because of improper disposal, but also their use in the first place. The following section discusses the existing and emerging alternatives to the generation and disposal of industrial waste.

[73] Note that these data are preliminary.

[74] OECD, Portal on Per and Poly Fluorinated Chemicals, “About PFASs”.

[75] “‘I don’t know how we’ll survive’: the farmers facing ruin in Maine’s ‘forever chemicals’ crisis”, The Guardian, March 22, 2022.